You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Uncategorized’ category.

Interview with Mr. Cuketka, Part II

When I ask how successful he’s been with Projekt Vesničan, Martin says proudly that he’s only set foot twice in a supermarket. (Once for dishwashing detergent, and once for white rum and limes.) Most of his food now comes from a CSA begun by one of his readers, Vanda Švihlová, owner of the café where we’re sitting. The CSA subscription is 275 Czech crowns (about $15) a week for a box of organic-certified vegetables. Martin shows me the contents of one of the boxes: spring onions with giant bulbs, fennel, parsley, carrots. “The basic idea behind the veggie box,” he explains, “was to cut out the middleman.” The trickiest part about Projekt Vesničan “is the logistics. You have to pick the sources and manage everything. But it’s worth it—definitely.”

Martin’s ethical streak extends to his insistence on keeping his blogging separate from his newspaper and magazine pieces. “It’s hard to stay independent,” he says of food writing in the Czech Republic. “The advantage of the blog is that I retain my integrity. If I feel that something is good, or extraordinary, I have no problem saying, ‘You must taste this!’” The blog, he says, taught him that readers are very sensitive, and can sniff out a food writer compromised by the lure of a free meal, or free products. “No one told me to act like this,” Martin says quietly. “I looked up a code of food-writing ethics, and I see how unethical writing bends the article [in favor of advertisers].” As a food critic, he declines to make kitchen visits or talk to the chef.

“The Czech Republic is so small,” he continues. “There are 50 top chefs, maybe fewer.” It’s increasingly difficult for him to remain anonymous, given the visibility of his profile in the press. “In 2007, at the Prague Food Festival, no one knew me. In 2008, a few people knew me. In 2009…” He trails off, but it’s clear that, as he says, his days as a newspaper food critic are numbered.

In contrast, Cuketka.cz allows Martin “perfect control” over the advertising, and he loves that freedom. When I ask him why he went to such lengths, in the forum section of his blog, to explain the advertising in depth to readers, he confesses, “I was afraid that the spirit of the blog would die. But it was ok with readers as long as the style and topics didn’t change.” This kind of transparency has created an online community that moderates itself. The comments, Martin notes, are “clean, polite, not off-topic, and not harsh; there’s fantastic discussion. That’s the number one thing about my readers—the interactivity.” Martin says he can raise a topic or question, and readers will take off with it. Cuketka.cz shares its readership, by Martin’s estimates, with about twenty other food blogs in the Czech Republic.

At one point, Martin recalls, the demand for “Cuketka schwag” became so great that he produced about fifty buttons with the Cuketka logo and offered them to readers—with one caveat: readers would set their own prices for the buttons, and the proceeds would go to a charity of their choice. It cost 1,900 Czech crowns (a little over $100) to produce but raised 9,500 crowns (about $510). In 2008, Martin began to organize Cuketka.cz meetings—one of which was a cupping at Bio Zahrada, by La Boheme Café, a local specialty-coffee roaster.

For the future, Martin says the most important thing is to secure continued sponsorship for the blog. When I inquire whether he’s working on a book, he shakes his head and tells me with excitement that something online and interactive is in the works.

It’s hard to measure the reach of one food blogger’s influence on the evolution of the Czech food scene. One telling indicator, however: shortly after Kuciel became a key proponent of CSAs, the CSA shares in Prague sold out entirely.

Next:

Great-Grandma Manion's Apple Dumplings

Interview with Mr. Cuketka, Part I

Most visitors to Prague know it as a city of cathedral spires and no-nonsense peasant food, not as a city undergoing a food revolution. Yet a few blocks from traditional-style restaurants dishing out roast pork, dumplings, sauerkraut, and beer in mass quantities, Czech food writer and restaurant critic Martin Kuciel is quietly leading the revolution, online—in his words, “provoking” his country and his generation to think differently about what they eat.

A look at the front page of Martin’s blog, Cuketka.cz, reveals its diverse interests: there’s a detailed, four-part recap of this year’s Prague Food Festival; a how-to on yokan (azuki-bean paste) with a photo of the result glimmering in a pan; an introduction to Czech food month; and an update on Projekt Vesničan (“Villagers’ Project”), Martin’s long-term reader-oriented experiment in living as a locavore.

Four years after launching what is now the top Czech food blog, Martin continues to blog, contributes independent restaurant reviews to the Czech weeklies Týden and Respekt, and writes a column for Apetit Magazine. As of June, he’d obtained monthly sponsorship from a series of cooking-related advertisers, a shift that allows him to focus full-time on writing and photographing. Yet Martin is not interested in succeeding only in financial terms. What sets him apart from many food bloggers, and what has made him an object of fascination in Czech media, is his passion for ethical and local food, for ethics in food writing, and for nurturing an active community of readers he describes, beaming, as “perfect.” The result is a blog unlike any other in the Czech Republic, and, arguably, anywhere.

Martin grew up in Ostrava, a heavily industrial city in the northeastern part of the Czech Republic. His grandparents worked in Ostrava’s steel mines, and his parents were first-generation college graduates. “I was never really a ‘foodie,’” he says over coffee one mid-June afternoon in Bio Zahrada, an organic-food shop and café in the Vinohrady district of Prague. “The blog is about the transition from being a non-foodie guy to being a foodie guy.” (As inspiration, he cites The Amateur Gourmet.) Even more unlikely is Martin’s own background: he graduated with a degree in medicine in 2004, but, he admits, he “never had any really serious intention to practice medicine. I was searching for another subject. After two years, I came up with [food writing].”

Initially, he says, the blog was just for fun. (The Cuketka logo—a smiling, be-toqued zucchini—and Martin’s forum comments, sprinkled liberally with smile emoticons, retain the whimsical feeling of the original format.) But as the blog grew, and as he began to write for print, Martin realized, he says, that “[t]here was a huge gap in food writing, so I started to take writing more seriously.” He slowly shifted the focus of the blog, and the kind of writing he was doing there.

The role of the blog, Martin emphasizes, is to provoke. “The nature of the Czech consumer is conservative,” he explains. “It’s hard for him to eat something exotic when he’s used to his Turkish coffee and svíčková.” (Svíčková is a classic Czech dish of boiled meat with vegetable sauce, garnished with whipped cream, a slice of lemon, and berry jam.)

Martin’s readers, who represent an increasing number of Czechs, want more. “Czechs travel, and they want to taste exotic things here, no matter what. It’s important to taste things, here, of good quality,” he insists. “Once you taste something good in its original form, you can never go back.” Take homemade pasta, Martin argues with a grin: once you eat it in Italy, you want to make it at that same level once you return home. You’ll always remember your first taste of real Italian pasta—and his theory is that you’ll never be willing to settle for less if you are passionate about food. (Italy is foremost on Martin’s mind: the newest appliance in his kitchen is a pasta machine.)

That Czechs have long had to settle for lower-quality goods in supermarkets, and have been, in his words, “vulnerable” to marketing campaigns for subpar products is implicit in Martin’s insistence on quality. Projekt Vesničan is an attempt to counter this; here’s is a man who’s read his Pollan. “It’s an experiment [that] started four months ago,” he says of the project. “The first intent was to help readers cook at home with seasonal and local produce, to disconnect from supermarkets and factory food, and to buy direct from farmers.”

As an example of what Projekt Vesničan rejects, Martin describes commercial egg farming in the Czech Republic. “There are 10 million hens: 4 million are for private use, and 6 million are for commercial use. 97% of those 6 million are battery hens.” (Martin notes that, beginning in 2012, battery hens—known as “laying hens” in the U.S.—will be banned in the EU.) Like farmers-market devotees everywhere, Martin and his readers are not just in search of better eggs, but better everything—and local everything: produce, milk, meat. “The milk is sometimes sour,” he concedes with a smile, “but it’s alive.” Meat is two to three times more expensive than it is in the supermarket, since it comes from high-quality farms, he says. For bread, Martin bakes his own—and favors the No-Knead method, which he discovered through Mark Bittman’s New York Times column. Cuketka.cz may be geared solely at Czech readers, but has a distinctly global outlook.

[More to come–Part II, Apple Dumplings, and Chlebíčky Spread–in the next couple of days.] :)

In compiling recipes for the cookbook, it’s a gentle surprise to find that some seem to have been border-hopping for generations. Vepřové žebírko s jabulky a cibulí, for example, is Pork Chops with Apples and Onions–a winter staple in American families as equally as it is in Czech families, as it turns out. “You grew up eating this, too?” we exclaim a few times an evening, stumbling over cookbooks.

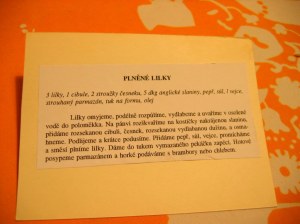

This Stuffed Eggplant recipe is one of these.

Plněné lilky (Stuffed Eggplant)

Stuffed Eggplant

2 small eggplants (or 1 large eggplant)

vegetable or olive oil, for frying

1 onion, chopped

2-3 cloves garlic, minced

3 strips bacon

salt and pepper

1 egg, beaten

grated Parmesan

vegetable oil

Clean and halve the eggplants. Scoop out as much flesh as possible, without leaving a hole. Arrange eggplant halves in an oiled baking dish, season with salt and pepper, and bake at 400°F for 10-12 minutes or until slightly browned.

Meanwhile, chop eggplant flesh and sauté in oil in a non-stick pan on medium-high heat until browned on all sides. Remove and set aside. In the same pan, sauté bacon until fairly crispy; remove, chop, and set aside. Add onion and garlic, and sauté for a few minutes before returning eggplant and bacon to pan for a final toss together. Turn off heat, season mixture with salt and pepper, add egg, and mix together.

Divide the mixture between the eggplant halves. Reduce oven temperature to 375°F, and bake for 20 minutes. Sprinkle with Parmesan, and serve with potatoes or bread. (Rice or orzo would also round out the dish.)

Since I added basil and oregano to the eggplant, bacon, and onion mixture, the result is a Czech-Italian hybrid…

One American-sized eggplant would have fed a whole family, but little Italian ones would be ideal as appetizers.

There’s a strange beauty in stuffing vegetables–everything seems to fit together, but there’s a lot more of it than when you started. This filling lends itself to additions of everything from sautéed mushrooms and fresh breadcrumbs to crabmeat, sundried tomatoes, or chopped nuts.

Exactly where this recipe came from is a mystery, to me. It’s one of the dozens from my mother-in-law’s card file; many of them probably came from a larger work published by the Kalich house (where J’s mother worked as an editor) in the late ’80s or early ’90s. After J’s mother’s death, though, there was little cooking from scratch going on in the family, except when Dana came for Christmas, and the recipes sat on a pantry shelf in clear plastic strawberry cartons. When we moved in, I asked J’s father if we could have a shelf for our arborio rice and jumble of spice jars, and when I moved aside a woven-reed breadbasket, I discovered the stack of recipes that reminded me instantly of my mother’s collection.

Whenever my brother and I complained as teenagers, my mother would admonish us, “You’re from pioneer stock. Chin up.” This, and the stories from the branch of the family that trekked out to the Colorado prairie on a covered wagon in the 1880s, was enough to silence us for a while.

My great-grandmother’s family settled on the eastern plains, in Kit Carson County, just past the line in Colorado where a summer afternoon can turn humid and fierce with storms. My grandmother spent part of her childhood there, an only child hunting for arrowheads and avoiding rattlesnakes, before her family moved into Denver.

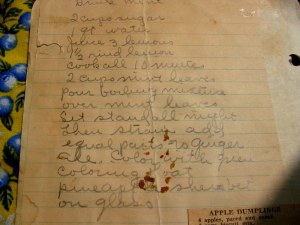

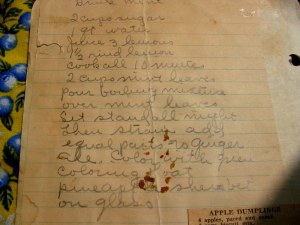

One of a handful of recipes from my great-grandmother, this one for a lemony mint drink is the kind of thing that would improve a summer afternoon far from town.

Mint Drink

Mint Drink

2 cups sugar*

1 quart water

juice of 3 lemons

rind from 1 1/2 lemons

2 cups mint leaves

ginger ale

Cook sugar, water, lemon juice, and lemon rind for 10 minutes. Pour boiling mixture over mint leaves. Let stand all night. Strain, and add equal parts to ginger ale. Color with green food coloring. Float pineapple sherbet on glass.

[*1 cup is enough, unless you don’t plan to use much ginger ale.]

The base is a lemon-flavored simple syrup; you could update it (if you wanted to) by using thyme instead of mint…but the lemon-mint combination is ideal for summer.

Lemon and mint steeping in a giant bowl. Our apartment smelled like an herb garden.

The results, the next morning…

At first, I resisted adding the green food coloring. Then I decided that the effect demanded to be seen…and it was just as impressive (and startling) on a drab New York windowsill as it would have been on a sun-bleached Colorado porch.

I loved this discussion of sugar and salt (cukr i sůl) as a Czech idiom on Radio Praha’s SoundCzech program, from reporter Rosie Johnston: click.

The last paragraph explains how the Czech slogan for the country’s EU presidency, “osladit Evropě,” which literally means “to sweeten Europe,” has a completely different figurative meaning.

Well. Dort purists and Czech readers, you might want to avert your eyes.

Not quite Pařížský dort (Parisian Cake)...

I know. It doesn’t look quite the way it’s supposed to. As I was reading and translating the recipe, which had its own discursive way (a way I’m fond of), I took a wrong turn and wound up with something that looked like a brownie mixture. So I baked it. And that became the second layer. The cake that ultimately emerged in my New York kitchen is a plump, round cousin of the thin, square Czech version.

“You made a Pařížský brownie,” my husband laughed, when he saw the results.

“But didn’t your mother make this?” I asked him. “Where did this recipe come from?”

“Probably my great-grandmother’s bakery in Telecí,” he replied, getting out a fork and taking a closer look at the slices.

“So your mom didn’t make this?” I pressed.

He sank down on the couch and eyed the four layers. “No, it’s much too heavy.”

“And complicated,” I said.

It’s all part of the journey, right?

Below, I give you the real translation…

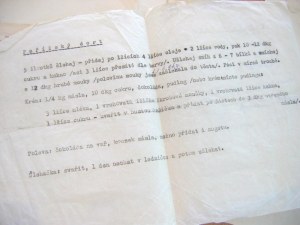

Pařížský dort (Parisian Cake)

Cake:

5 egg yolks

4 tbsp. (lžice) vegetable oil

2 tbsp. (lžice) water

1/2 to 3/4 cup (10-12 dkg) sugar

3 tbsp. (lžice) cocoa (or just enough to add color)

6-7 egg whites

3/4 cup (12 dkg) flour

Chocolate-cream topping:

1 package chocolate pudding, prepared according to package directions

Alternatively, according to the recipe, you can mix together 2 softened sticks of butter (250 grams), 1/2 cup (10 dkg) sugar, and chocolate.

Glaze:

baking chocolate

a bit of butter

nougat (optional)

Whipped-cream topping:

1 cup heavy cream, whipped into stiff peaks. (The recipe advises preparing and leaving in the fridge for one day before using, though I’m not quite sure why. Maybe the peaks hold better?)

For the cake:

Mix the egg yolks with the oil. Add the water, sugar, and cocoa.

In a separate bowl, beat the egg whites until firm. Gently add half the flour to the egg whites; add the rest of the flour to the yolk mixture. Mix the contents of both bowls together, pour into a buttered 8 x 8″ pan, and bake at 200°F for 30-45 minutes or until done.

For the chocolate-cream topping:

Make pudding. Set aside.

For the glaze:

Melt the baking chocolate and add a bit of butter (less than one tbsp.). Let cool.

To assemble:

Add the chocolate-cream (pudding) to the base layer. Pour the glaze gently over. Top with whipped cream.

Pařížský dort: Part One

To be honest, anything involving making sníh, snow (egg whites whisked into firm peaks), by hand, makes me nervous. I lack the stamina that prior, mixer-less generations of women from all sides of my family no doubt had in spades. Still, ever since seeing this kind of cake, and its frappé-like layers in the windows of the Ovocný Světozor patisserie in Prague, I’ve wanted to try to make it.

Pařížský dort (Parisian Cake)

I’ll include a translation of the recipe in Part Two, but here’s Jakub’s mom’s recipe, again.

I started with the base, first:

I’m fairly sure those egg whites should have been much fluffier, but the base turned out decently:

Finished cake base on the left; butter melting for the next layer, right.

The chocolate-butter-cocoa layer revealed itself to be brownies in the making:

And here’s two of the cake’s layers, so far. It was only after taking that out of the oven that I realized that those neat slices of Pařížský dort in Prague all had right angles. My kitchen and I are round-cake-pan kind of people, though, so this version looks for all the world like a chocolate tart:

It’s now sitting in the fridge with a note attached: “Please don’t eat yet–work in-progress.”

Later today, I’ll add the chocolate-cream layer, and then the whipped cream top, at some point. The recipe advises that the whipped cream should be made one day ahead, stored in the fridge overnight, and then used the next day. Someone with a broader culinary background than me can weigh in on why this might be.

Since it promises to be another broiling week here in New York, I’m excited to try one of my great-grandmother’s recipes for a mint and ginger-ale drink topped with pineapple sherbet:

Any project like this has to be able to withstand the “So what?” test. That is, sure, it’s fun to page through old recipes, but so what? What’s the bigger significance?

I’m not sure I can supply a watertight answer to that yet, but the process of pulling together disparate strands of a family tree, this way, and using recipes as a vehicle for storytelling and characters, is what interests me most.

Who are these people?

What did they like?

Why have these recipes been saved for nearly a hundred years?

Plus, this kind of search is relatively easy for anyone to do, as nearly everyone has access–through a file of old recipes, or via oral tradition, which just comes to you as you’re standing in the kitchen–to a family story like this.

The results are in, and the majority of the votes went to the multilayered chocolate extravaganza, the Pařížský dort (Parisian Cake)!

So! The shopping list: cream, cocoa, flour, butter, chocolate, and milk. (There’s a reference to pudding in the recipe, too–as a substitute for something–which I need to figure out.)

I’m also working on tying together both halves of this project; the other half, which is arriving from Colorado, in batches, includes recipes from my mom’s collection and going back to my great-grandmothers’ recipes. Many of these formed the basis for the cookbook my mom–acting as publisher, editor, and designer–made me as a wedding gift. It was the best gift ever: a book bursting with recipes solicited from friends and family, which I’ve consulted nearly every day since receiving it. Other items–winter coats, glassware, books–had to be left behind or shipped, when we moved each time, but that book has always been the first thing into my carry-on, wrapped in a shawl to protect it during the long hauls from the U.S., from Israel, and from Prague.

Among the great-grandmothers (on both the Czech and American sides) whose recipes underpin this project, there’s a heavy bias toward baked goods: pies, cakes, and cookies. One handwritten recipe, a trio of cakes (including a Lady Baltimore cake that I’m hoping to make) from my great-grandmother has a note at the top in her curly hand–“These are my specialties,” a résumé of sorts. First, the Pařížský dort, and then the Lady Baltimore cake!

It occurs to me that I don’t have a kitchen scale, a crucial piece of equipment to European bakers…

Here’s the one in my husband’s dad’s kitchen, in Žižkov, tucked away.

Kitchen scale in Prague

Et voilà: here it is, unfurled and in use (when I was making the incredibly tough French sugar tart):

Recommendations for U.S. kitchen scales, anyone?

Incidentally, the second and last of my Jauntsetter posts is up: “Prague Nightlife: The Best Places to Eat, Drink, and Dance.” (I confess that I’ve spent way more time wandering around cafes and patisseries in the Letná neighborhood than I ever have at the Akropolis.)

The gracious folks at Jauntsetter are featuring my Prague tips and favorites as part of their Trip Pick, this week: Perusing Prague. There’s another one coming up, later this week, and is really a Patisserie Tour with some walking thrown in.

And the first batch of Italian/Irish/American recipes arrived in the mail today, courtesy of my mom! :)

Looks like I’ll be making Pařížský dort (Parisian Cake), which I’ve wanted to do. Let’s hope the monsoon that’s swirling around New York doesn’t wreak havoc on the egg whites. (Or is that just a myth?)

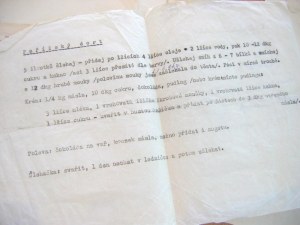

The problem with old recipes is that they fly off the table in the barest breeze. It’s a cool morning, here, and I’m up earlier than I’ve been in a long time. After two cups of coffee from La Boheme Cafe (Prague!), I’m sifting through J.’s mother’s recipes, or trying to, but they skip out from under my fingers and float off toward the hallway, light as onion peels.

Pařížský dort (Parisian Cake)

This one is for Pařížský dort (Parisian Cake): cream, oil, water, sugar, cocoa, 6-7 egg whites, topped with a creamy mix of butter, sugar, chocolate, and pudding. The base is chocolate cake; the middle, that creamy chocolate mix, finished with a chocolate glaze and a knot of whipped cream. Should I try this? Six to seven stiff-peak egg whites in New York humidity? What do you think?

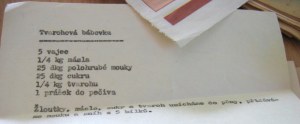

Tvarohová bábovka (Tvaroch Cake)

Bábovka,a light and springy cake, is one of the first things I learned to make, even before we moved to Prague. J.’s Aunt Dana makes a spectacular one called Prezidentská bábovka, which is flecked with chopped bits of chocolate, and somehow manages to slide out of a Bundt pan, completely intact.

But I also learned how to make this from a Czech friend I met while both our families were living at the Weizmann Scientific Institute, in Israel. Katka and I were both married to postdocs and (as such) our visas prohibited us from working, so we became quick friends while trying to adapt to Israeli and Weizmann culture. For a while, Katka was teaching me Czech, but she couldn’t stop laughing at my pronunciation. Since she had a hearty, infectious laugh, I didn’t get very far in my studies. But the friendship grew, and one of the first things she gave me was a bábovka recipe written from memory. When I made some comment about that, she just rolled her eyes and said, “Erin, every Czech girl knows this recipe.”

A handful from the pile…

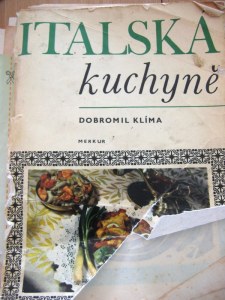

Well-loved Italian cookbook

Králík po Livornsku (Rabbit alla Livornese)

The Italian cookbook, from 1968, falls open to this page, and is weathered (like all favorite cookbooks) with floury fingerprints and sauce blots. Years of the thick cooking air have begun to darken the edges in a kind of sepia watermark.

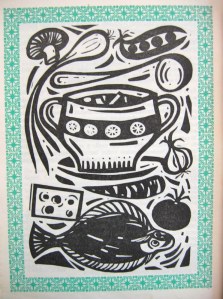

Woodblock illustration from the Italian cookbook

It takes a long time to realize, if you’re immersed in this cookbook, that there are no photographs–just these mesmerizing green-and-black block graphics.

Kuchařka naší vesnice (Our Villages' Cookbook)

I’m fairly sure this is the Czech Joy of Cooking: that indispensable cookbook you run to for everything from how to truss a turkey to how to eat soup dumplings politely. What? That’s not in Joy?

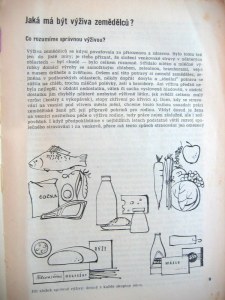

Introductory pages, Kuchařka naší vesnice

The food pyramid, Czech-villager style. Five components for proper nutrition, reads the caption. Something each day from every group. Reasonable and logical. (And 739 pages long.) The book was printed in 1967.

Čočka (right under the fish) are lentils. The word also means “lens” in Czech, and when my father-in-law used to talk about photography, one of his passions, while making lentils, it would confuse me to no end.

Čočka is close to another word, kočka, “cat.” On more than one occasion, that first year in Prague, J.’s dad would be making lentils for Sunday lunch, and I would come in, offer to stir the pot, and exclaim, “Cats! I love cooked cats!” My father-in-law and my husband would fell on each other, laughing.

I need to make a few things, this week. What would you like to see? Cast your vote below!

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](https://i0.wp.com/img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png)

Recent comments